The government has already been making moves in this space. From August 2022, the introduction of the Register of Overseas Entities has required overseas entities owning UK property to declare who their beneficial owners were, including non-UK companies.

The move indicated to the wider market a tighter grip on compliance by the government.

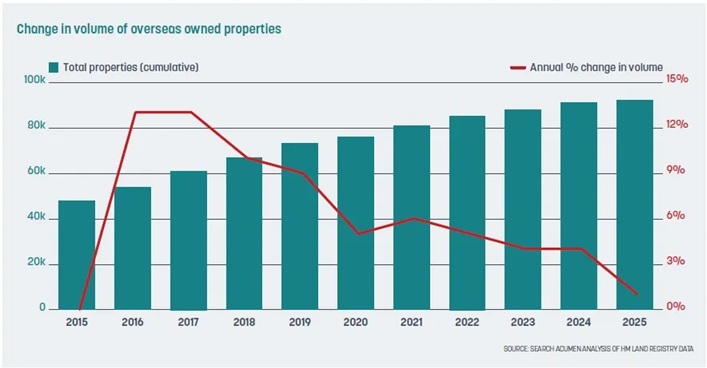

However, there are concerns that tighter transparency rules are deterring foreign investment. For example, according to legal-tech provider Search Acumen, 2025 saw 3,834 fewer property titles registered under overseas-owned companies than in 2022 when the register was introduced.

Andrew Lloyd, director at Search Acumen, says: “That had a chilling effect on some buyers and may have contributed to some properties being offloaded quickly.”

The data, seen exclusively by Property Week, shows that the number of properties in England and Wales purchased by overseas-based companies has fallen to a 10-year low.

“This tells us two things,” says Lloyd. “That either investors and the wealthy are buying assets and storing capital outside the UK, which is a troubling sign that our global appeal may be in decline, or that our property transaction system is becoming more stringent, noting increased transparency measures and anti-money laundering regulation in recent years deterring illicit purchases. The likely answer is a bit of both.”

Lacy Gratton, a partner in the real estate corporate team at law firm Taylor Wessing, observes that the deterrent effect is “real and measurable”. She adds: “Research shows new property purchases by tax-haven companies fell by approximately £255m monthly following the register’s introduction. The regime has been effective precisely because it’s public facing – investors know their ownership will be scrutinised, not just by regulators but by journalists, NGOs [non-governmental organisations] and the public.”

Lloyd says: “While reducing anonymity must be a good thing, it may have in turn deterred some investors. This, combined with rising interest rates, higher borrowing costs, falling yields and slow capital growth, has likely made speculative investment less rewarding.”

Overseas ownership of UK property Infogram

According to Lord Dominic Johnson, who served as minister of state in the Department for Business and Trade for the Conservatives between February 2023 and July 2024, deterring wealthy international investors is a “serious problem for the economy”. He warns: “Although I was responsible for taking the transparency legislation through parliament – and I still believe we need clean and safe access to the UK economy – the interpretation of these rules has created the perception that Britain doesn’t want international capital.

“We’ve pushed transparency to the nth degree, requiring very high levels of public disclosure. That doesn’t always work for investors who simply want a degree of discretion – not because they’re dishonest, but because they want privacy in how they deploy their capital. I think this should have been considered more carefully when the legislation and regulations were designed.”

Some of the impacts include: property prices no longer reflecting global value; liquidity falling; and a reduction in circulating capital. “That means fewer homes built, fewer properties available and ultimately higher costs for British citizens,” he adds.

Review of the register

The government is set to review the effectiveness of the register in 2027, opening an opportunity to strike a balance between encouraging investment and enforcing transparency. A spokesperson for the Department for Business and Trade (DBT) says: “The Register of Overseas Entities aims to combat money laundering by increasing transparency in the UK property market. We keep a close eye on the register’s effectiveness and impact, which will be a key focus of a post-implementation review in 2027.”

Lloyd says striking the right balance would take “political courage”. He adds: “You could design a new policy framework to make the system fairer but, in the process, many corporate actors would feel the pain – because they’ve built business models around the current rules.”

Johnson believes “there’s a lot we could do.” He says that as well as revisiting how the register works, the government could reduce taxes on international investors, reinstate incentives that once attracted non-doms, revise stamp duty and rethink the current trajectory of building regulations – such as the two-staircase rule for buildings over 80m.

“When I was in government, I argued strongly against changes to leasehold that caused uncertainty in a multi-billion-pound asset class,” Johnson says. “Moving the goalposts is fatal for investment. Property rights and the rule of law are Britain’s biggest competitive advantage. Undermine them – even with the best intentions – and you weaken the market, damage the economy and ultimately harm the livelihoods of people in the UK.”

Despite the launch of the Register of Overseas Entities, a lack of transparency on overseas ownership of UK property remains an issue. Earlier this year, Property Week identified the top 100 largest landowners in central London (p26, 18.07.25). One surprising finding was that just 5% of commercial properties were registered to overseas owners, even though vast volumes of foreign capital had flowed into UK real estate over the years.

As the data could only track ownership through parent companies, not ultimate beneficial owners, the low figure likely reflects years of opacity about ownership, with foreign capital frequently entering the market via UK-registered entities.

Lloyd says: “The UK has two competing narratives: one is about wealth inequality and the other is about asset accumulation as a core function of capitalism. Understanding the market is crucial.”

Top jurisdictions for oversea UK property owners, by number of properties Infogram

There are, however, still legal mechanisms that allow beneficial owners to remain obscured despite the register. As Gratton says: “When overseas entities are held via trusts, beneficial ownership information about trust beneficiaries and settlors [people who create trusts] is reported privately to HMRC rather than publicly on the register.”

A ‘registrable beneficial owner’ is defined as someone holding more than 25% of shares or voting rights. Gratton points out that “sophisticated investors can structure ownership to stay just below this threshold, avoiding disclosure entirely while maintaining effective control through shareholder agreements or other arrangements”.

Nominee arrangements also remain common and legal. Firms can report nominee owners and directors, often professional service firms, rather than ultimate beneficial owners.

Meanwhile, the value of property under overseas ownership has jumped from £15.9bn in 2015 to £125bn today. According to Search Acumen, 2017 saw one of the largest annual rises in titles registered by overseas companies, at 6,955 properties, while 2018 saw the highest value of new properties registered, at £16.2bn.

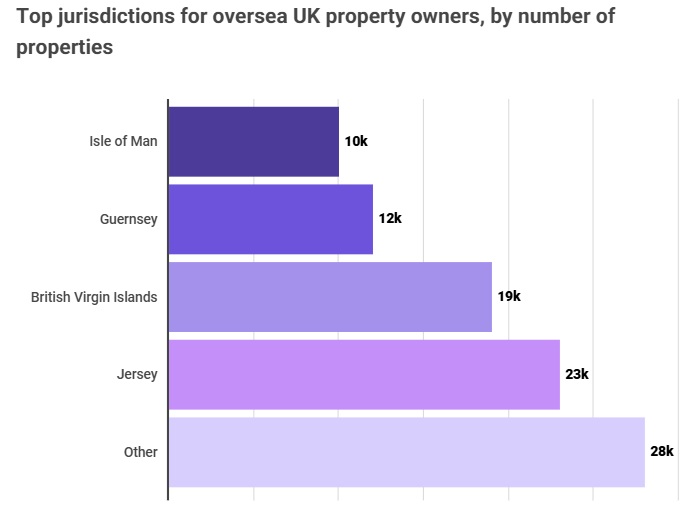

Jersey is the top country on the register with the highest volume and value of properties registered under overseas company ownership, holding £57bn worth of assets.

Although Jersey-linked companies account for 25% of all overseas-owned properties, their holdings are significantly higher in value, representing nearly half of the total by worth.

Lloyd says: “Previously, much of the overseas ownership was based in jurisdictions like Jersey, the Isle of Man and Singapore, which often pointed to British citizens being the ultimate owners.”

However, with new transparency laws, much of the advantage of owning via an offshore structure is gone, especially if the reason was to conceal ownership. “So, unless the motive is tax minimisation, there’s now much less benefit to structuring ownership that way,” Lloyd says.

Gratton says the UK’s approach is “notably more aggressive” than that of many competitors. Following the 2022 European Court of Justice ruling that publicly accessible beneficial ownership registers could violate human rights, several EU jurisdictions have pulled back from public transparency.

The UK government explicitly rejected this approach, confirming that transparency trumps privacy in its view.

‘Competitive dynamic’

As Gratton says: “This creates a competitive dynamic. While the UK tightens transparency requirements, jurisdictions like Dubai, Singapore and certain US states maintain more flexible regimes. The question is whether the UK’s moral high ground translates into competitive disadvantage for attracting legitimate capital.

“Crucially, research found no strong evidence of price effects from the register, meaning that while the policy affects new investment on the margin, it hasn’t led to substantial changes in housing prices faced by the domestic population. This is important – it suggests the regime is targeting the right behaviour without creating broader market distortions.”

She adds: “The UK remains a top-tier destination – the rule of law, market depth and London’s global status ensure that. But it might not be the default choice. The combination of Brexit friction, additional taxes and aggressive transparency requirements means the UK must work harder to attract international capital.”

Follow us on Twitter

Follow us on Twitter

Follow us on LinkedIn

Follow us on LinkedIn